Story By: Cat Acree

Photography: Daniel Meigs

Nashville Design Week 2018

Perhaps long ago, on some dark night, Nashville native Ashley Balding reached through a crack of time, some portal of futurism, and pulled back the furiously innovative designs of Ona Rex, her line of luxury women’s wear.

From malleable dresses with slippery ruffles and paracord spines, to elbow-sweeping capes that belong in Lando Calrissian’s closet, to her iconic, freshly peeled gallery pendants, Ashley Balding’s designs demand a world to be built around them. I’d say that Balding is an alien that’s fallen to Earth, but as she shares in our conversation, that would be a terrible thing to say.

How did you begin your design practice?

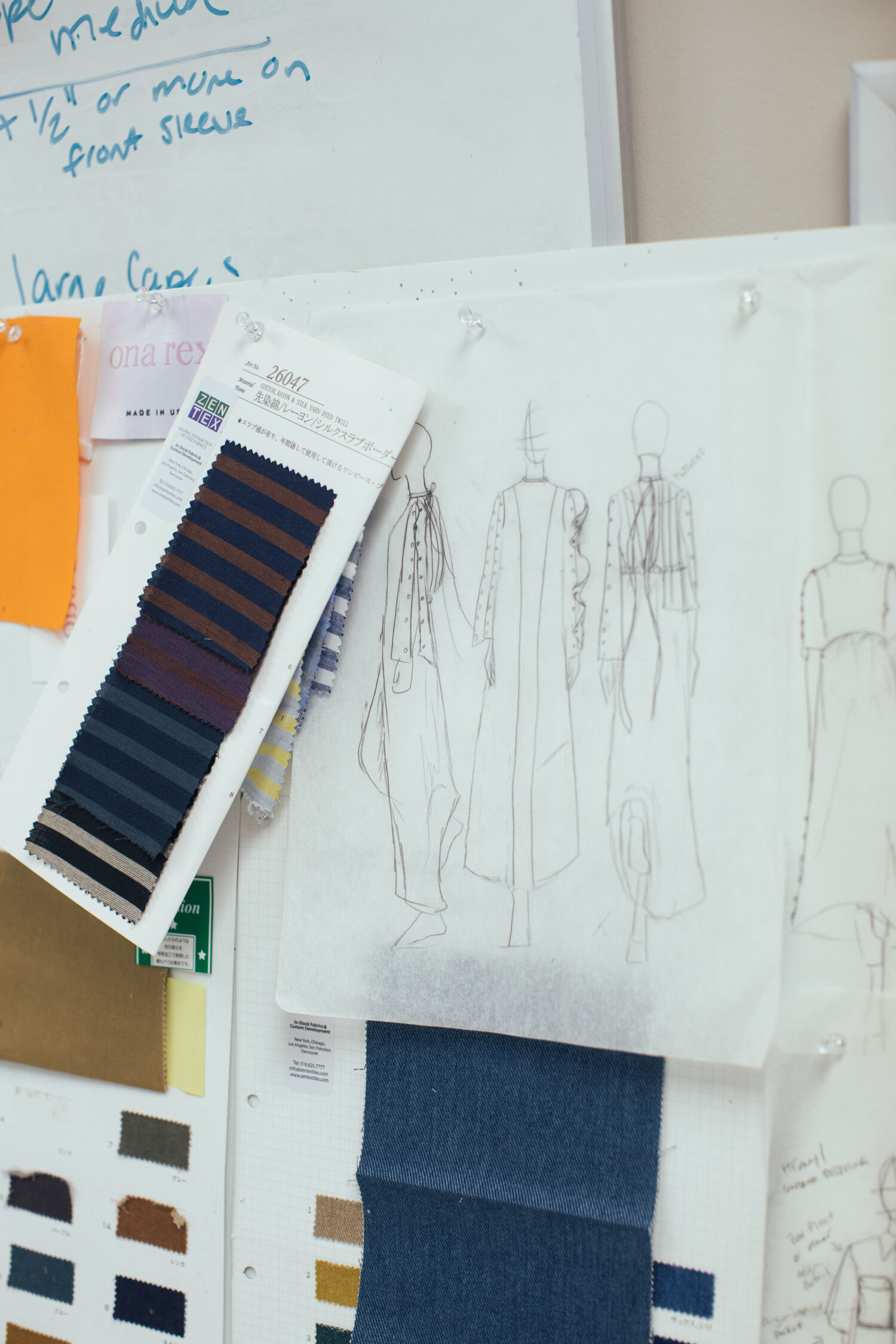

My plan was to study fibers in school. I knew that I liked fabric, but design was not on my radar. I ended up leaving school and taking several years off, but I kept coming back to fashion. I went back to school [at O’More College of Design], still not thinking about design, but once I got into classes, I realized my brain was a little bit different from the people around me. I felt kind of stupid about it at first, until I realized it was a good thing.

I had no plans for starting my own line. It was something that I thought I would do later, like when I was middle-aged. But I just got so angry when I was out of school. There was such a small group of people here, doing something really good, but it was so tiny. I knew that I could add to that, only differently.

Did your definition of design change throughout that experience?

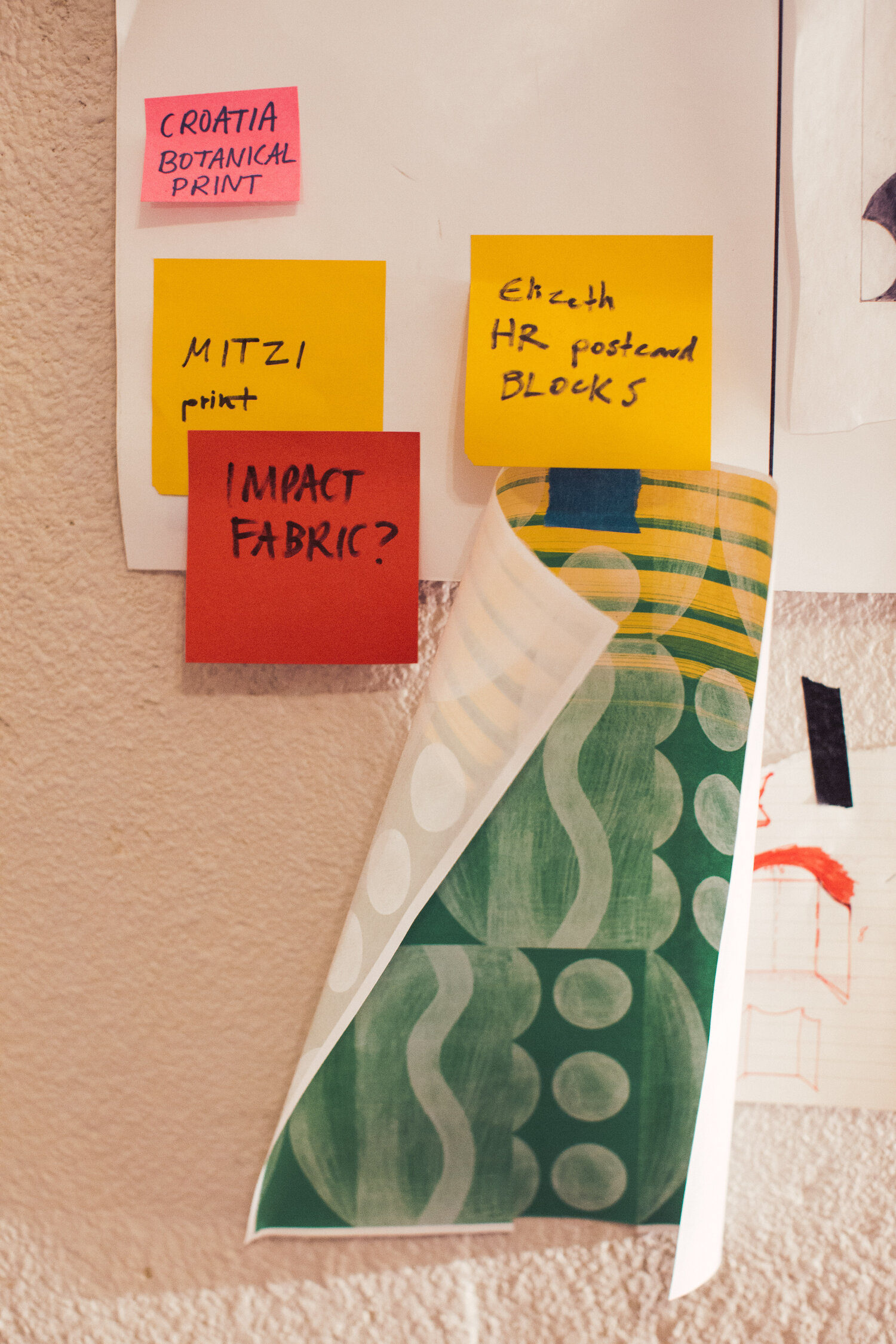

There’s a lot of clothing out there—technically, someone’s designing it—but there’s no garment innovation. That’s what I’m excited about. I’m not an expert and I’m still learning how to do that. I think my paracord stuff was the first time I was like, this is where it’s going where I want it to go. That’s not something you see everywhere. It changes shape on your body. If you want it to be a giant, puffed-up shirt, you can scrunch it all the way up, or if you want it to look like a more normal dress, you let it down. That’s the kind of stuff I get excited about—trying to think of how these flat shapes come together on your body and can totally transform how you feel. To me, I think that’s the most important aspect of design, is creating, innovating, reinventing.

What three things most influence your design?

I am obsessed with science fiction. It probably plays into the part of my brain that likes science, and the part that likes weird. I get excited about fantasy worlds and outer space. I think there’s something exciting about futuristic things. Aliens, creatures, monsters—I’m terrified of all those things. It’s the most gut-wrenching fear I have. If an alien walked into the room, I would die. There’s just something about the human form in a completely different, abstract view.

I love structure—it could be a building, it could be sculpture—but there’s something about 3-D forms that are really exciting to me. I like the design process of linear things coming together, and I like to think of garments in linear perspectives. And color is a huge part of what I do. I can drive down the street and see a color, and it sparks an entire thing in my brain.

How do you characterize your role in the Nashville fashion world?

I just want to fuck everybody up. If I’m going to expend the emotional and mental energy of doing this—because it’s not easy, and a lot of times it’s very disheartening—I’m not going to make white T-shirts. I think it’s true in any creative field that you can feel overlooked sometimes, you can feel misunderstood sometimes. It’s really hard. What’s the point anyway, so I’m just going to do something how I want to do it. I’m learning to be brave about it.

It feels the most complimentary to me when someone says I’m doing something totally different, or that they’d never expect me to be from Nashville. Truly everyone here has been very supportive and are very excited about what I’m doing, but I don’t sell much here. I never have. I’ve always said that, that this isn’t my market.

Is that why you made the “Base” line? With the simpler shapes and colors?

Yes, and it sold the best.

It’s like a painter who makes a smaller, more affordable painting to pay the bills.

I’ve learned that if people have a taste of something they feel safe in, then they’re more likely to be like, if I like how I look in this, and that’s like a little more adventurous . . . I’m trying to put cheese out for people.

What do you think is your role in the larger Nashville world?

I would like to represent a modernized city. I grew up here, and I was very fortunate that my parents were very worldly and were excited to take us to other places. It’s important to me that I not be a representation of what Nashville was twenty years ago. There are good parts to that—I love tradition, I love heritage—but I want to represent a forward thought.

Is this a one-woman operation? Any plans for collaboration?

Brett Warren is my very unofficial business partner. I would never say that it’s just me doing this. He does all my photography. He’s my art director and my greatest support. He sculpts my necklaces, so he’s very involved, and I think we are each other’s muses in that way. In the way that I’m a little different, he experiences that in his field as well. It’s easy for us to be like, we’re doing something different, and it’s uncomfortable, but if we can help each other go along that path, we do.

Blaque of PORTmanteau jewelry, we will have a collaboration at some point. We’ve been working on one for a while, but it hasn’t become what we want it to be yet, so it just hasn’t happened. I would love to get into many different aspects of fashion, but I love her stuff so much.