Story By: Cat Acree

Photography: Daniel Meigs

Nashville Design Week 2019

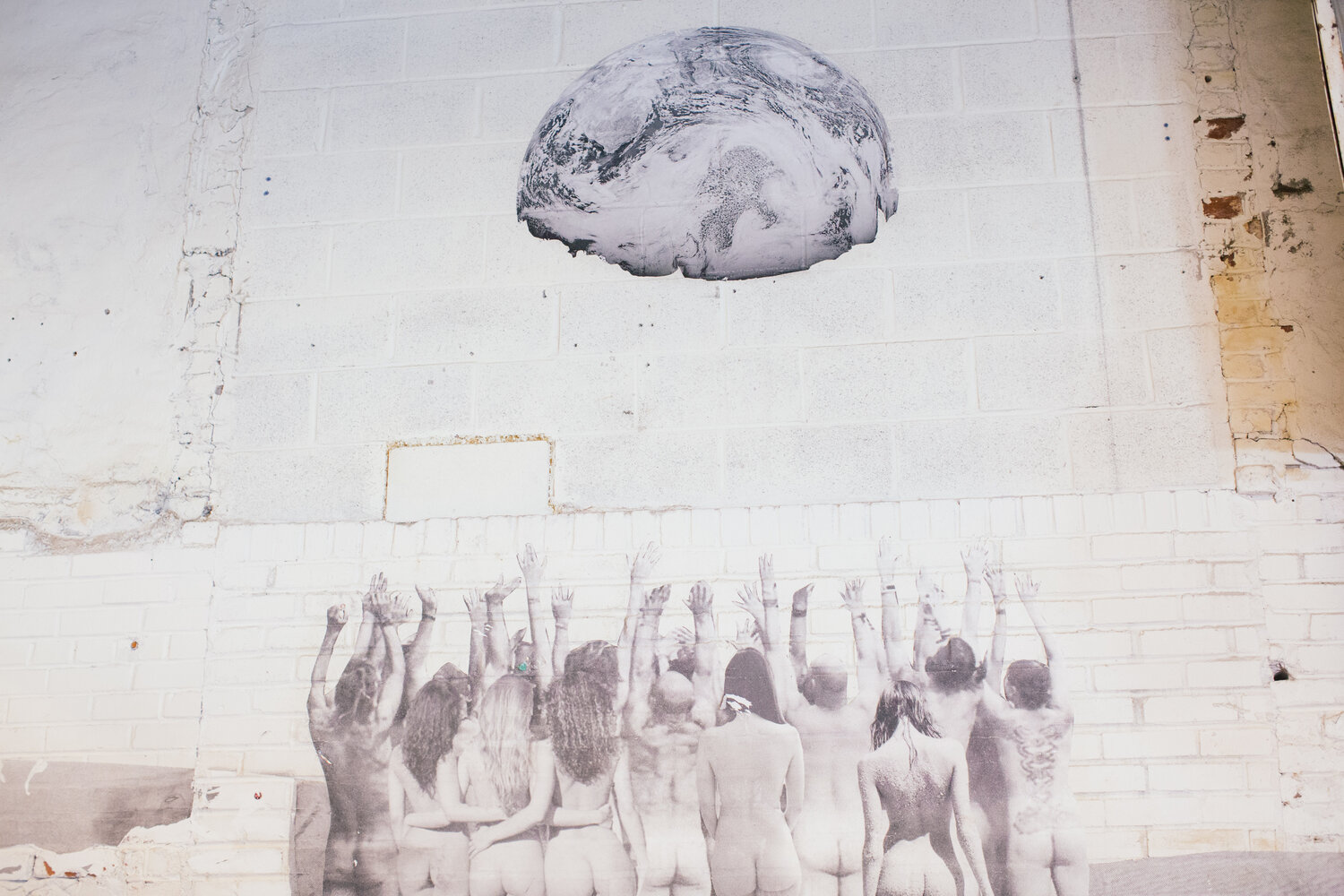

Picture a tangerine—it’s bright, juicy, practically glowing with freshness. But like eating a delicious fruit, that glow is temporary, as after tartness comes the possibility of rot. There’s a dark side to everything, and despite the effusive cheeriness of Galerie Tangerine’s name, its exhibitions hardly feature art that is so simple.

Owner Anne Daigh brings her own artistic sensibility and love for darker, complex art to the sunshine-filled walls of Galerie Tangerine. Daigh opened Anne Daigh Landscape Architect in 2010, which became Daigh Rick Landscape Architects when she partnered with Wade Rick in January of 2018. For the past two years, the firm has operated an art gallery from their airy landscape architecture studio, located in a former repair shop in the Gulch. There’s art everywhere—from the foyer where clients enter to the studio where the firm’s architects get down to business. It’s a gallery that has no remove from the day-to-day of normal life, from the realities of workspaces and meeting rooms. Art doesn’t just occupy these rooms; it exists as a part of the living space. Principal and founder Daigh, along with office manager and gallery coordinator Lilli Robinson, recently opened their doors to Nashville Design Week for a studio visit.

On the utterly charming name.

Anne–

One day I was folding my clothes, and [on] one of my tank tops, the name tag inside, the brand was Tangerine. I saw it and was like, that’s going to be the name of the gallery. Our first artist, actually—his name was Henry Rasmussen, a brilliant artist, amazing guy—he suggested we switch it. It was going to be Tangerine Gallery, and now I can’t even imagine saying it like that. And [the neon sign is] his handwriting. . . . And then once I got comfortable with “Galerie Tangerine,” I started thinking about how one of my favorite songs of all time was Led Zeppelin’s “Tangerine.” And then also, I was looking into it and the word tangerine actually means “prosperity.” Everything about it just makes sense.

On the voice of the gallery and the work of Rasmussen, who brought such a melancholic style of art into this space.

Anne–

There’s something about the rawness of [melancholy]—we all experience it, but the gallery is my way of expressing it through the art that we show. . . . I can’t quite put my finger on it, but Galerie Tangerine is more about fresh and new, not necessarily happy. There’s a dark side to everything, a yin and a yang. That’s kind of how I like to design, too. I like to create, in the landscape architecture side of things, hard and soft elements. That creates balance, acknowledging the hard and the soft.

On how the gallery fits into the landscape architecture firm.

Anne–

Art is the basis for all design, in a way, and [the gallery] provides a different platform for us to explore that. I’ve actually had an issue with buying art. [Laughs] I love curating and finding new artists, so this was a vehicle or forum for that, so other people can experience it. Rather than it just being my own personal art, this is a way to share that with other people. It does feel like an access into my heart.

Lilli–

It’s beneficial on both sides. On the landscape architecture side, we work really closely with interior designers who are oftentimes searching for art for their clients, so it builds relationships.

“There’s a dark side to everything, a yin and a yang. That’s kind of how I like to design, too.”

On choosing their artists.

Anne–

A lot of galleries have rosters, and [artists] sign a contract with them. Once a year they’ll have a show, and they’re represented by that gallery. . . . The artists that we select and find is an organic process. We only do it for a quarter, and then we move on to the next artist—and what I realized we’ve been doing is we’re providing a platform for these artists to get their name out into Nashville. We’re not so hooked on the fact of representing them. It’s kind of a stepping stone for them, for other galleries to pick them up and represent them.

On what makes Galerie Tangerine different from other galleries.

Anne–

The landscape architecture is what’s allowing us to be risky and do what we want with the art, because the sale of this art is not dependent on paying the rent. That’s pretty critical. All we hope to do is break even after each show.

Lilli–

It’s more enjoyable because we don’t have that pressure.

Anne–

It could be really stressful if we were dependent on selling art, a certain amount each month. That almost could take the fun out of it.

On their perspective on Nashville’s art scene.

Anne–

I’m a little disappointed by it. It hasn’t been as accepting as I would’ve hoped to putting riskier stuff out. The fact that we’re able to be more risky, we’re able to put out stuff I love—I quickly learned that [people felt] this is cool and all, but this is nothing I’d want to hang on my wall. Nashville is not quite as edgy as some other places. . . . I will say that we’ve gotten to know the art community well, and they’ve all been kind.